J-J Jacotot, a charlatan after all?

Joseph Jacotot was an 18th century French pedagogue espousing a radical way of teaching which he called universal education (enseignement universel). I’ve written about him and the book that reclaimed him for modern audiences, Jacques Ranciere’s The Ignorant Schoolmaster, before on this site and on goodreads.

Now, in my day to day life as a simple educator, I compartmentalise: try to make the most of Jacotot’s principles while waiving any hope for purity, to prevent a nervous breakdown. This usually works out fine, but I’m slowly being faced with another existential hurdle: the pressure to write a book, as a step on the ol’ career ladder.

So I once again had the cursed impulse to ask myself: what would JJJ do?

I remembered reading about Jacotot’s experience teaching all sorts of subjects he was wholly ignorant of, and even publishing books on these topics along the way. So I looked up his Mathématiques (1827) and found it on google books…

It’s… amazing. This is a “maths book” unlike any I’ve ever heard of. But if you think about it, there’s nothing else it could have been. Let me run you through it:

- pages 5-41: JJJ’s messages to officers and cadets of the École normale, where apparently he’d been applying his method for 10 years now. Contains a jovial introduction of his universal education principles to a cohort of newly emancipated youths.

- pages 42-64: a series of narrative “scenes” where the universal method is challenged by various fools and doubters, who are set straight in dramatic (or, JJJ calls it, romantic) fashion.

- pages 65-130: extracts from official reports testifying to the efficiency of JJJ’s method. Leading into JJJ’s correspondence with members of the royal court, including Prince Frederick of the Netherlands himself. He seems to ingratiate himself by training officers for the army, then (at page 96) drops the 17 commandments of universal learning onto Fredrik, who responds positively (page 100). And it carries on from there…

- …to pages 131-137: VOILA LE FAIT. “Here’s the facts,” he says, “are you convinced or do you need a better king?” But alas, the social order is not fit to recognise JJJ’s merits and disseminate his method, even though His Majesty has explicitly declared this as His wish! Gripping stuff, right?

- pages 138-159: since the lowly Netherlands have shown themselves not up to the task, JJJ now addresses ALL NATIONS to stand up against the corruption and abrutissement in institutional education. Including a “REPORT MADE, ON THE MOON, ABOUT THE EDUCATION OF EARTH” …irresistible, isn’t it?

- pages 160-225: “examples of bad reasonings” against the method. A protracted diatribe which should delight any Jacototians in the audience, while stoking despair in the hearts of students of, you know, mathematics: the book is almost over, what’s going on here?

- page 226: JJJ’s resolution on how to deal with know-it-all savants, who question him without having studied his method.

- page 227: his final appeal to learners everywhere who lack means but not human dignity.

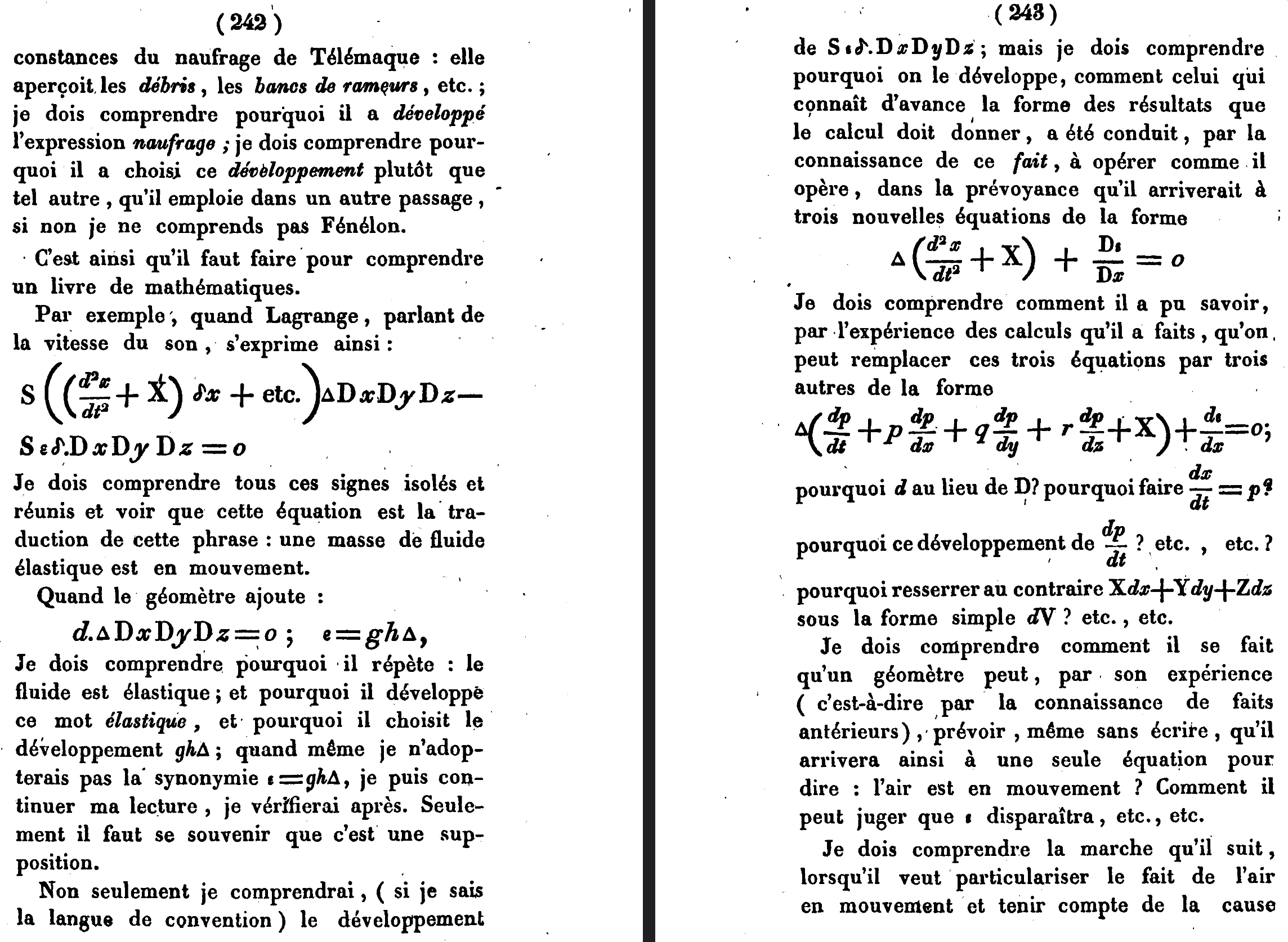

- page 228 onwards: endnotes and an appendix. Just as we’ve given up all hope, we see NOTE II, “pour les Géomètres”, and a two-page spread which I’ll reproduce in full below.

This is the only bit of the book which reasonably looks like “maths”.

I’m not saying there isn’t any mention of mathematics in the rest of the book, there is, but nowhere near as often and as applied as Les Aventures de Télémaque, his source material of choice. Since “everything is in everything”, you’re meant to use the same formula to get good at maths as you do to learn a language.

Now, I’m a fan of peer review skepticism but it’s hard to justify a book like this, with this title, being published in the modern era. And even in the 1820’s, were there such “fake” textbooks just floating around?

You gotta think, Jacotot was no fool, he knew this is a 260-page propaganda pamphlet (for a worthy cause!) masquerading as a maths book. But why put it out it like this? Some theories:

- the actual contents were common knowledge back then, the title was required for publishing

- the title is a troll move, to trick people into finding out about universal learning

- the whole thing is just a paper-wasting exercise for career advancement, the book wasn’t actually meant to be read seriously

The last one I find the least likely, since so much of the book actively addresses the audience. Yet, a clear yearning for legitimacy runs through the entire thing.

In the end, I don’t think Jacotot is a charlatan, but it’s hard to say this book helps his case… Nor does it aid me in my plight: even if publishing such a book would be possible today, I could never write one.

Still, I might at least somewhat try.